Main story – Roop family honors its heritage in founding of Gilroy Hot Springs

19th century guests paid $7 for a one-week stay at famous health spa resort

Published in the October 31 – November 13, 2018 issue of Gilroy Life

Photo by Marty Cheek

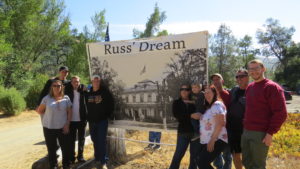

From left to right, Jennifer Nelson (5th generation), Joshua Nelson (6th), Jacob Nelson (6th), Dylan Lawlor (6th), Shawna Lawlor (5th), Garrett Mabery (6th), Lisa Beckemeyer (5th), Jason Mabery (5th), Jim Mabery (4th), and Addison Beckemeyer (6th). They are descendants of George Roop who founded the hot springs.

Winding their way along Roop Road, local history buffs traveled to explore the Gilroy Hot Springs site deep in a canyon east of South Valley. Among them were fourth-, fifth- and sixth-generation descendants of George Roop, a pioneer settler who founded the famous resort 150 years ago for vacationers to soak in and imbibe the mineral-rich waters.

At the dedication ceremony at the hot spring’s annual event that opened the site to visitors Sept. 29, the Roop family members unveiled a large banner showing an old photo of the resort’s grand hotel crafted in an ornate Italianate Victorian style. Superimposed in front of the hotel image was Russ Mabery and his mother, Florence Roop Mabery, and a terrier pet dog. The great grandson of George Roop, Russ long held a dream to bring back the resort for public use, said his daughter Jennifer Nelson.

“It’s important to honor my dad’s memory, and it was his dream to see this (hotel) rebuilt,” she said. “As he was growing up his mother always talked about the hot springs and coming up here and being an 18-year-old woman running such a grand resort. She had such great memories of being here and running it. It’s just important for me to carry on my dad’s dream.”

Docent Karen Pogue holds a pail of water from the hot springs for a visitor to smell. The mineral water has a sulfur, or rotten egg, odor. Photo by Marty Cheek

The hotel burned to ashes in 1980 from an arson fire and the ground where it stood is now used for visitor parking. Scattered among the hills of the Gilroy Hot Springs are a dozen cabins where vacationers stayed.

Along the dirt path are changing rooms for women and men near the site of the hot springs. For decades, pine, oak and sycamore trees have grown wild among the decaying buildings. In 2003, the Nature Conservancy purchased the 400-acre property and donated it to become part of Henry W. Coe State Park.

Touring the grounds in the open house’s guided tours by Pine Ridge Association volunteers, visitors got a glimpse of the hot spring’s past glory as a premier get-away spot for the rich and powerful. During Prohibition, prominent politicians, bankers and investors came to the hot springs to socialize, drink liquor and play cards, said Nelson’s sister, Lisa Beckmeyer.

“There’s a lot of rich history of historical nature – bootlegging and gambling,” she said. “George Roop made this a destination for really grand parties, so it’s sad to see it wasn’t able to be kept up. But now it is part of the park system, which is kind of comforting, too, because now maybe we can see (the property) taken care of and more people can see what was hidden back here.”

“There’s a lot of rich history of historical nature – bootlegging and gambling,” she said. “George Roop made this a destination for really grand parties, so it’s sad to see it wasn’t able to be kept up. But now it is part of the park system, which is kind of comforting, too, because now maybe we can see (the property) taken care of and more people can see what was hidden back here.”

South Valley writer Ian Sanders explored much of the Gilroy Hot Spring’s history in his book “The Mineral Springs of Santa Clara County.” The local Indian tribes gathered at the hot springs to enjoy the mineral waters which came out of the earth at a temperature of about 112 degrees. The water contains sulfur, which gives off a slightly pungent rotten egg smell. Other ingredients include iron, magnesia, and soda.

Roop partnered with William Olden to build a road — called Roop Road — to provide access from downtown Gilroy to the resort’s two-story hotel built in 1868 at a cost of $12,000. So popular did the hot springs grow that in the mid-1870s the partners added a third story on the hotel.

Visitors stayed in 32 guest rooms, ate in three large dining rooms seating 200 guests and enjoyed shooting pool in a billiard room for men. As the resort’s popularity grew, cabins were built and named after states of the American union. At its height, 500 visitors could enjoy the resort, taking hikes through the hills during the day and dancing in a pavilion at night. The cost for room and board was $7 for seven days.

Visitors stayed in 32 guest rooms, ate in three large dining rooms seating 200 guests and enjoyed shooting pool in a billiard room for men. As the resort’s popularity grew, cabins were built and named after states of the American union. At its height, 500 visitors could enjoy the resort, taking hikes through the hills during the day and dancing in a pavilion at night. The cost for room and board was $7 for seven days.

During the Roaring ‘20s, the resort was a spot for San Francisco politicians to come for illicit liquor and Thursday night poker parties — as well as secret romantic trysts.

When the Great Depression hit, the number of overnight guests declined significantly. Kzuyzaburo Sakata, a Watsonville farmer, purchased the property in 1938 with a dream of making a more formal resort. He added traditional Japanese bathing amenities, a Shinto Buddhist shrine, a Japanese teahouse and Japanese gardens. It was renamed Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs.

When Japanese-American citizens were placed in internment camps in 1942, Sakata was among them. His Caucasian business associates maintained the resort grounds.

When Sakata returned to Gilroy in 1945, he offered the use of the hotel and cabins to 60 Japanese-Americans families and individuals released from the camps as a refuge to start to rebuild their lives in World War II’s aftermath.

The Gilroy Hot Springs served as the first home to Laura Domínguez-Yon who was a baby when her parents arrived after leaving the Posten, Ariz., internment camp. “Is it the water or the tranquility or the isolation? Whatever it was, we turned up here,” she said.

In the 1950s, the hot spring pools brought people back to soak, but the resort never returned to its “hey-day” years, she said. (Those pools were in recent years filled with sand for liability reasons.)

The health spa fell into disrepair and Sakata sold the property. The resort was used on a private basis for many years after. In the 1990s, there was an attempt by a Japanese developer to turn the land into a golf resort/health spa, but environmental concerns by county officials stopped that.

Today, Gilroy Hot Springs is protected by the state as a California Landmark. Much work has been done to repair the cabins or keep them from falling apart. Unfortunately, vandals still damage these historic buildings.

A group is trying to form a nonprofit organization to raise money and bring awareness to the preservation efforts of the site, said Domínguez-Yon. She organizes the fall and spring open house events to encourage people to visit the hot springs site and learn about its colorful history.

“Our goal is to restore the site and protect the public access to Gilroy Hot Springs. I don’t imagine that it will return to the hey-day when they had 300 to 500 visitors a day,” she said. “We’re not imagining anything like that.”