Nonprofit profile: Nonprofit for Gilroy Hot Springs raises funds with the hope of opening the historic site to the public

The goal is to raise about $95,000 for camping, cabin rentals and springs

![]()

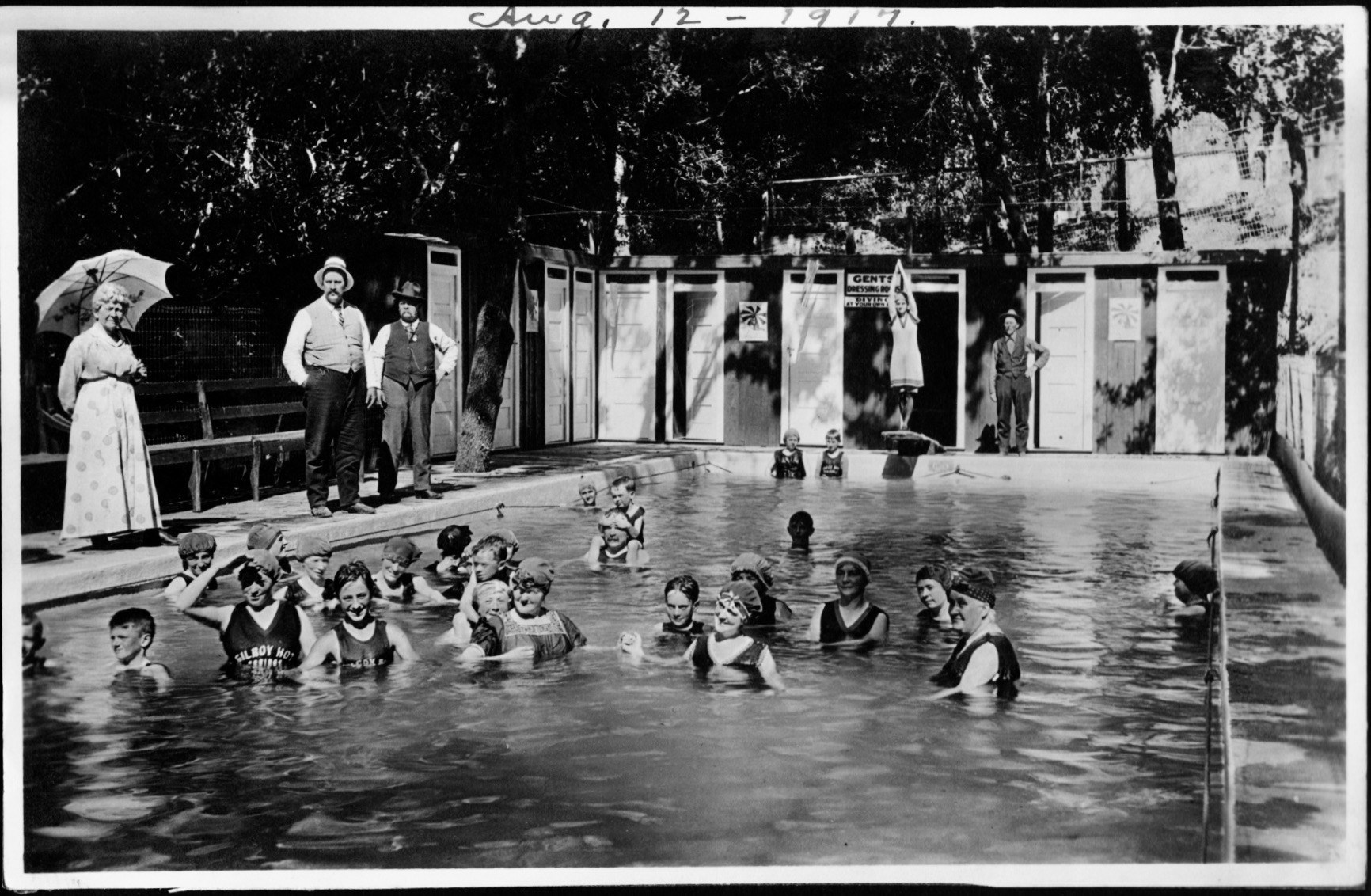

This photo from Aug. 12, 1917, shows people enjoying the Gilroy Hot Springs. Photo courtesy Gilroy Hot Springs

By Marty Cheek

More than half a century after it was closed in the 1960s, Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs is well on its way to being re-opened for public use. Local residents recently enjoyed a special event to help raise $95,000 to make the famous resort site accessible for camping and cabin rentals.

Called “Soak It All In: A Day of Water, Wine and History of Gilroy Hot Springs,” the fundraiser was a three-part, self-paced tour held Saturday, Oct. 9. It was sponsored by the Gilroy Hot Springs Conservancy, the Gilroy Museum, the Gilroy Historical Society, and Satori Cellars.

The first part of the tour started at the Gilroy Museum where guests viewed a special exhibit and learned the history of the springs, said Lucie Vogel, president of the Gilroy Hot Springs Conservancy board.

In the second part of the fundraiser guests took docent-led walking tours at the hot springs site. “You get to see the springs and the cabin restoration and everything that’s going on,” Vogel said.

In the second part of the fundraiser guests took docent-led walking tours at the hot springs site. “You get to see the springs and the cabin restoration and everything that’s going on,” Vogel said.

The third part of the tour was held at Satori Cellars on Buena Vista Avenue. Guests received a boxed lunch prepared by Gilroy chef Mark Segovia. Guests 21 and older were invited to a wine tasting.

The Gilroy Hot Springs Conservancy was formed as a nonprofit in March 2020 with the goal of restoring the site at the end of Roop Road in the Diablo Range east of Gilroy. The site is part of Henry W. Coe State Park, purchased by the state in 2003. Because the buildings are in a delicate state, public access is limited. For years, the spirit of the hot springs and potential for preservation has been maintained by the Friends of Gilroy Hot Springs, a committee under the Pine Ridge Association, which is an interpretative nonprofit serving Henry Coe.

The Gilroy Hot Springs Conservancy is a partnership with California State Parks to restore, maintain and operate the springs as well as the historically protected structures on the property.

The Gilroy Hot Springs Conservancy is a partnership with California State Parks to restore, maintain and operate the springs as well as the historically protected structures on the property.

“Planned services for the public include mineral hot springs soaking, camping, restored cabin rental, and recreation,” Vogel said. “The reopening of Gilroy Hot Springs will bring healing, commerce and community to Gilroy and the south Santa Clara Valley.”

The group has goals for the next stage after the site is open, she said.

“We’re planning on doing incrementally more restoration of the historic structures,” she said. “We have 27 protected structures on the property. Our goal is to restore all of those. That will give us a number of functioning cabins which we can then rent out for revenue.”

Two dilapidated bath houses will be a major project to rehabilitate, she said.

Over the years, there have been discussions of bringing the site back to its original resort glory, including rebuilding the large hotel, which burned down in 1980. One local architect estimated that the price tag for a full rehabilitation would be $40 million.

Over the years, there have been discussions of bringing the site back to its original resort glory, including rebuilding the large hotel, which burned down in 1980. One local architect estimated that the price tag for a full rehabilitation would be $40 million.

“There are a lot of limits in terms of infrastructure,” Vogel said. “There is county approval that we would need in terms of improvements and capacity. There has been some talk about rebuilding the historic hotel. We do have the blueprints. We could completely re-do that if we ever get the money together.”

In its heyday, the springs resort was a popular destination, bringing people from throughout the Bay Area. The land was purchased in 1866 by George Roop and William Olden with a goal of creating a vacation site for well-heeled San Franciscans to escape the cold weather in that city during summer. A train from San Francisco deposited guests in Gilroy where they boarded a dedicated stagecoach for a 10-mile ride to the resort that could accommodate up to 200 guests a day.

In its heyday, the springs resort was a popular destination, bringing people from throughout the Bay Area. The land was purchased in 1866 by George Roop and William Olden with a goal of creating a vacation site for well-heeled San Franciscans to escape the cold weather in that city during summer. A train from San Francisco deposited guests in Gilroy where they boarded a dedicated stagecoach for a 10-mile ride to the resort that could accommodate up to 200 guests a day.

In the 1920s, the springs developed a reputation for bootleg liquor, slot machine gambling, and Thursday night poker games that drew large crowds. Swimming parties, Saturday night dances, and local service club specials were also prominent during this time. The Great Depression of the 1930s caused resort activity to dwindle.

In September 1938, Kyuzaburo Sakata, a successful local Japanese lettuce grower in Watsonville, purchased the property and announced he would build a Japanese garden to be designed by Nagao Sakurai, of the Imperial Palace.

In September 1938, Kyuzaburo Sakata, a successful local Japanese lettuce grower in Watsonville, purchased the property and announced he would build a Japanese garden to be designed by Nagao Sakurai, of the Imperial Palace.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Sakata and about 120,000 other Japanese Americans were placed in internment camps. The businessman’s dream never happened. Following World War II, many Japanese Americans found a temporary place to rebuild their lives at the former resort.