Guest Column … with Tina Pershing Baine: ‘Aromastory’: The overlooked history of an underdog community

Book explores the history of Gilroy’s nearest neighbor to the south

![]()

By Tina Pershing Baine

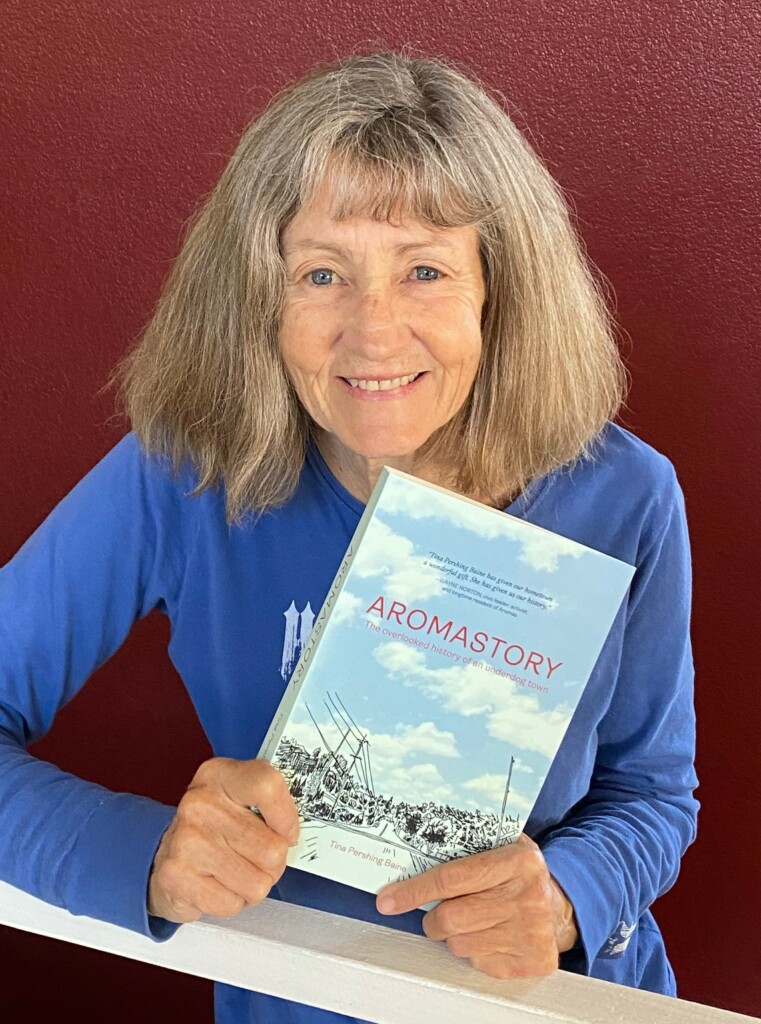

Tina Pershing Baine

When Gilroy was incorporated in 1870, shortly after the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the land that would become Aromas was dotted with only a few small farms. But, thanks to the foresight of a few Gilroy men, that sparsely settled area would become an enduring rural town.

When the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Gilroy in 1869, its arrival was celebrated with much “jollification,” according to the Monterey Gazette. The rails would connect Gilroy not only to San Jose and San Francisco, but also with the rest of the country. In 1871, the S.P., anxious to connect with the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad in Southern California, continued construction southward toward Hollister.

Santa Cruz County leaders mounted a vigorous campaign to persuade the railroad magnates to turn the tracks away from Hollister, toward the coast. One of those leaders was San Francisco attorney Nathaniel Chittenden, who purchased 6,000 acres in the southeast corner of Santa Cruz County in 1870 and partnered with four other men of means to build a railroad from Gilroy to Watsonville. When the S.P. eventually agreed to route their tracks toward the coast, Chittenden turned his energies to road-building, creating an extensive road system that connected ranches and mountain destinations and extending the road from Watsonville toward Gilroy. Chittenden Pass, carved over the centuries by the Pajaro River, was named for this forward-thinking entrepreneur.

Nascent towns and stations formed along the new tracks, including Sargent’s in Santa Clara County, and Betabel, Chittenden’s, and Logan in San Benito County. Farmers purchased land along the tracks and lobbied the S.P. for the construction of nearby depots to transport their cattle and crops by train.

In 1887, when Benjamin Bardue decided to sell his 1,200-acre ranch which straddled both Monterey and San Benito counties, it was purchased by the Gilroy Land and Trust Company. Bonds were sold to investors to raise capital for subdividing and marketing the property as a new community.

The front-men were George T. Dunlap and James C. Zuck — both wealthy civic leaders. Dunlap was the mayor of Gilroy and Zuck was the president of Gilroy Bank, and later elected state senator representing Santa Clara County. The development was dubbed “Samuel Rea’s Subdivision of the Bardue Ranch.” A major investor and prominent Gilroy rancher, Rea came to California from Ohio in 1852 via Panama — a voyage made more arduous when the ship nearly ran out of provisions before reaching San Francisco. Rea mined in the Gold Country for seven years, then moved to Santa Clara County, and eventually owned a 332-acre ranch outside of Gilroy where he raised stock and ran a dairy.

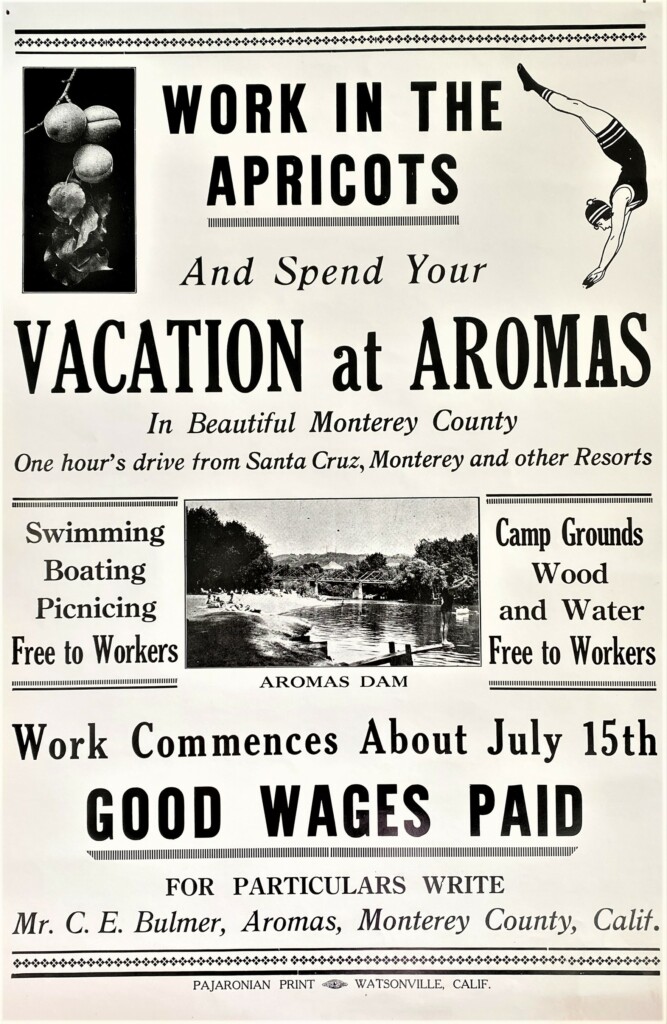

An ad in a local newspaper lauds the benefits of Aromas. Photo courtesy Tina Pershing Baine

The Bardue Tract was surveyed and mapped in November 1893. The plans were finally approved by Monterey and San Benito counties in 1894. Dunlap and Zuck set up a real estate office across the road from the railroad depot and created a sales brochure illustrating the various parcels for sale, including 38 farm-sized lots spreading out over the hills and 88 small residential lots in the flat downtown area. In December the Pajaronian newspaper reported, “The new town will be called Aromitas,” taken from the land grant Rancho Las Aromitas y Agua Caliente. The post office opened in 1894 with George’s brother, Jim Dunlap as the first postmaster and shopkeeper. When the application for the post office was finally approved, “Aromitas” had been supplanted by “Aromas.”

William and Rosa Kortright were some of the first buyers in the new subdivision. George Robbins — who would move to Aromas with his wife, Emma, soon after — recommended Aromas to the Kortrights when they were both living in Madera in the San Joaquin Valley.

“One day we were telling him how we would like to get closer to the coast, and he told us how he had spent the previous summer camping near a little place called Aromas and how nice it was,” Rosa said.

The Kortrights contacted Jim Dunlap at the post office, “And Jim said to come over in a hurry. He rented us a room for a blacksmith shop and right away we opened a store and there was no other store in Aromas for 12 years.” In 1897, Dunlap handed over the post office to the Kortrights, which they operated from their store WF Kortright General Merchandise with Rosa as the postmistress.

The Kortrights would eventually sell their second store, Pioneer Grocery, to Dolan Marshall in the 1940s. Marshall’s Grocery is still in business in the heart of downtown Aromas, with its original wooden floors and owners who know nearly everyone in town and have continued the tradition of giving out candy to children at Halloween.

Aromastory is the tale of Aromas, a small rural town (pop. 2,500) with an unusual name situated on the meeting points of three counties. One would expect a town called Aromas to be noticeably fragrant. After the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the dominant scent was a powerful whiff of rotten eggs as sulfur emanated from the crags along Highway 129 — unpleasant but still emblematic.

One hundred years earlier, farmers who hoped to associate Aromas with the sweet scent of ripe fruit, covered the surrounding hills in apricot orchards.

To increase the workforce and production they created a seasonal lake and posted “Vacation in Aromas” fliers to entice transient labor to harvest their burgeoning summer bounty. The apricots brought many people to Aromas and made a reputation for the town as the largest producer on the Central Coast.

Later, the townsfolk would veer away from hilltop orchards and the growth imperative, and Aromas became instead a quiet retreat for a new kind of resident. Commuter families discovered low-profile Aromas often by accident and were immediately charmed by its rural simplicity amidst the not-too-distant hubbub of city life and summer beach crowds.

Under the jurisdiction of three counties, Aromas has always struggled to be recognized and supported. Those struggles likely draw certain kinds of people to Aromas — do-it-yourselfers who are tough and resilient. They enjoy the town’s relative isolation as well as its close proximity to the urban regions surrounding it (except for the traffic, of course). This book is about the people who have been passionately drawn to this little town and have kept it going, and how Aromas fits into the larger story of the South Bay Area/Central Coast region of California.

For information about where to purchase Aromastory, which includes more than 250 vintage photographs and illustrations, visit www.aromastorythebook.com

Tina Pershing Baine has lived in Gilroy, and worked there as a newspaper photographer for seven years. She moved to Aromas in 1995.