Main story: Film festival brings veterans’ mental health issues to the screen

Film by Gilroy-born soldier highlights veterans’ invisible struggle with PTSD

Published in the March 20 – April 2, 2019 issue of Gilroy Life

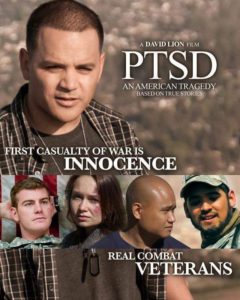

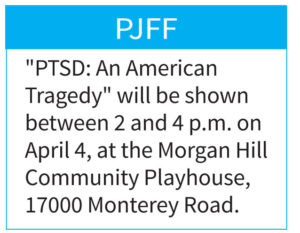

At the upcoming Poppy Jasper International Film Festival, audiences will see stories on the screen. One local filmmaker, Carlos Lopez, Jr., can’t be there. He committed suicide last June after suffering from years of post-traumatic stress disorder. His film “PTSD: An American Tragedy” will share his story.

At the upcoming Poppy Jasper International Film Festival, audiences will see stories on the screen. One local filmmaker, Carlos Lopez, Jr., can’t be there. He committed suicide last June after suffering from years of post-traumatic stress disorder. His film “PTSD: An American Tragedy” will share his story.

His father, Carlos Lopez Sr., said, “People don’t ask why when they hear about veteran suicide.” Yet, 22 veterans commit suicide daily, or 8,030 each year. That’s why Carlos Sr. and his wife, Juanita, are raising PTSD awareness.

“Our intentions are to honor our son’s work,” Juanita said. “We want to be hopeful. We want a better outcome for other veterans.”

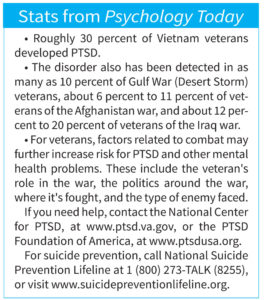

According to Psychology Today, PTSD is “a trauma or stress related disorder that may develop after exposure to an event or ordeal in which death or severe physical harm occurred or was threatened.” It affects about 8 million American adults. It’s frequently seen in conjunction with depression, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders.

Born in Gilroy, Carlos Jr. attended Nordstrom Elementary School in Morgan Hill. His family later moved to Elk Grove, where he graduated from high school and attended college. A month before Sept. 11, he joined the U.S. Army. It’s a family tradition. His grandfather is a World War II veteran. His father served in the Army. His younger brother is a Marine. From 19 to 24, Carlos essentially served three tours of duty in Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan

Photo courtesy Lopez family

Carlos Lopez, Jr. barbecues lunch on a hibachi grill during a tour in Afghanistan.

“He served honorably,” his father said. “But when he came out, he was not the same. He was easily agitated and angered. Frustration came quickly.”

After Iraq, Carlos Jr. immediately entered a film program, and was self-medicating.

Juanita recalled, “He was getting in trouble, drinking and partying.” Ironically, he entered the military to avoid that life. But he was going down that path, with the added emotional burden of war. “When it didn’t work for him anymore, he said, ‘I gotta leave.’”

He got a job overseas, doing security for U.S. troops in Kuwait. “He spent that year trying to decompress, as a civilian, in the towers of Kuwait. Working long hours, dealing with stress.”

That’s when he noticed symptoms of PTSD, like anxiety, guilt, fear, and thoughts of self-harm. For someone exposed to combat, those symptoms are common. But it was unpopular to discuss them or ask for help.

“Six months later,” Juanita said, “the military calls, tells him to come back and serve in Afghanistan.”

“Six months later,” Juanita said, “the military calls, tells him to come back and serve in Afghanistan.”

Struggling with PTSD, Lopez applied for an exemption. But the U.S. needed soldiers, and he was only granted 90 days. He deployed to Afghanistan, and two years became five. When he returned, Juanita observed, Carlos was hyper, falling into old patterns. “He came to us and said, ‘I need to follow my dream.’ He was yelling, on the verge of …” she struggled for the word, “whatever. He found the Los Angeles Film School and was gone in two days.”

He graduated, taking his anger with him. But he was developing what would become his legacy.

“To our amazement,” Juanita said, “he started to put this on film. He’d been in theater in high school and junior college. He could be on stage, projecting his anger and feelings.”

That controlled environment provided relief. He wrote the script for “PTSD: An American Tragedy,” and registered it with the Screen Actors Guild.

In the next six months, he recruited volunteers, including veterans, to make his 45-minute film on a shoestring budget. The unfinished cut he showed to his teachers was deemed too intense. “It’s a subject no one wants to hear about,” Carlos was told.

But it was what he had experienced.

Meanwhile, the actor/writer/director appeared on “Operation Repo” and had parts in “Captain America: The Winter Soldier,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” and “Bumblebee.” He lived comfortably in downtown L.A. with a bright future ahead of him.

Meanwhile, the actor/writer/director appeared on “Operation Repo” and had parts in “Captain America: The Winter Soldier,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” and “Bumblebee.” He lived comfortably in downtown L.A. with a bright future ahead of him.

Still, he hid a dangerous secret, one even his family didn’t comprehend.

“We thought he was managing it fine,” Juanita said.

However, in his final month, everything took a devastating turn.

In May 2018, Carlos told his father he’d finished his film. “He had it where he liked it,” Carlos Sr. said. “He’d edited it, added music. We were lucky to find it on his computer.”

In May 2018, Carlos told his father he’d finished his film. “He had it where he liked it,” Carlos Sr. said. “He’d edited it, added music. We were lucky to find it on his computer.”

Carlos Sr. wept when recalling a graphic, eight-minute torture scene, resulting in the death of a child. The Lopez’s speculated their son felt guilty about an event “in the heat of a mission.” In the completed film, it’s cut to two minutes. “That was his heart breaking,” Juanita observed. “He carried it with him until the day he died.” But that wasn’t all.

“There was a change in his prescription 35 days prior to his death,” Carlos Sr. remembered. “One day he told me, ‘I think my meds are off.’ That was June 18.”

Sometime in the evening of June 24, Carlos Lopez Jr. took a gun to the balcony of his apartment and shot himself.

Carlos sought help from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. But it was slow and insufficient. For two years, he tried unsuccessfully to get counseling. Eventually, he was given a three-month prescription for pills to ease back pain.

One of their side effects was suicidal thoughts. Four days after Carlos shot himself, a notice came. He’d been approved for counseling. Then another three months’ worth of his medication arrived.

One of their side effects was suicidal thoughts. Four days after Carlos shot himself, a notice came. He’d been approved for counseling. Then another three months’ worth of his medication arrived.

The Lopez’s know their son’s film isn’t easy to watch, particularly after learning his fate. “It will leave people stunned in sadness at the end,” Carlos Sr. said.

But it’s important for the family’s healing to spread the message Carlos Jr. wanted to convey.

“PTSD could never let him stop. Our veterans dying of PTSD are casualties of war,” Juanita said. “They survive combat only to die in their neighborhoods and communities. Our hope is that this film leads to people learning strategies to lead a better life. Get help. You’re not alone.”

- Third graders learn about conservation in outdoor classroom - March 13, 2020

- At 15, former South Valley resident Sierra Murphy’s star is on the rise - February 13, 2020

- 2020 Spice of Life award recipients truly care about Gilroy - January 31, 2020